The fiercest space race is not about getting back to the moon—it’s about allowing you to post a TikTok or watch Netflix on your phone anywhere around the globe, from the Atacama Salt Flats to the Khongor sand dunes in the Gobi Desert. To make this happen, two distinct design philosophies are at war, as companies build out the infrastructure needed to ensure every phone on the planet is permanently connected to the internet.

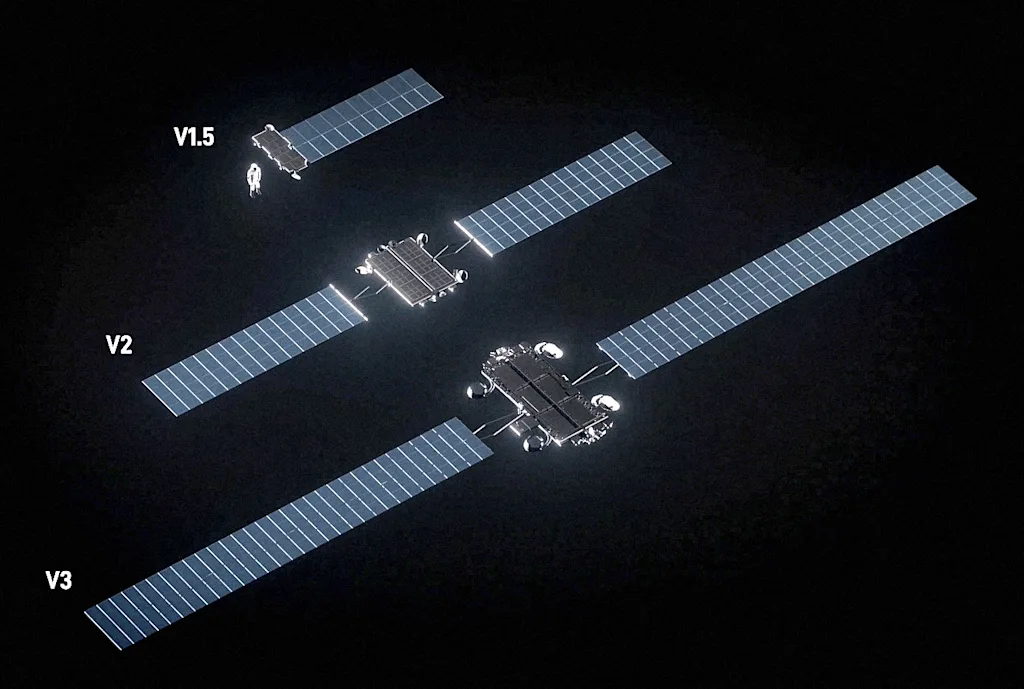

On one side is Elon Musk’s SpaceX/Starlink and the copycat companies that have followed in Starlink’s wake. Their approach is to invade space with tens of thousands of small satellites, creating a network of objects that blanket low Earth orbit. On the other side is a small Texas-based company called AST SpaceMobile, which believes it can provide better service with fewer than 100 gigantic satellites in space.

Both companies—along with Amazon and a handful of Chinese organizations—want to dominate worldwide wireless communications. The satellite constellation with the fastest service, widest coverage, best compatibility with 5G cellphones, and lowest operational costs will own how we communicate for years to come. Which approach prevails will have serious impact not only on the future of the internet but also the health of our planet.

A new space race era

Musk set off a new space race with his desire to rule low Earth orbit. SpaceX, which owns Starlink, launched its first satellite in 2019, providing broadband internet access to anyone with a large Starlink antenna and modem on the ground. Since then, it has put more than 9,000 satellites into orbit. The company projects it will eventually have a constellation of 34,000 satellites. After Starlink’s initial launch, competitors followed suit, including Jeff Bezos and his Project Kuiper—now called Amazon Leo—and the Chinese, whose plans include two large satellite constellations.

But there’s a fundamental problem with this mega-constellation design: Musk’s plan for space internet is a flawed, wasteful, and dangerous game of orbital Russian roulette.

Scientists worry that Starlink’s projected 34,000-satellite constellation will cause irreparable damage to the atmosphere. A large-scale constellation also dramatically increases the possibility of a space collision that could start a catastrophic chain reaction, destroying orbital networks that are crucial for our survival as a species.

Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist and spaceflight historian at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, has been documenting satellite launches in his newsletter, Jonathan’s Space Report. He believes there may be other, better ways to achieve global coverage via satellites—if we need to be doing it at all.

“I do personally have a preference for smaller numbers of larger satellites,” he tells Fast Company. “One of the reasons is the risk of space collisions. If you have 10 times as many satellites, you have 100 times as many close misses. So from that point of view alone, consolidating on a smaller number of satellites seems wiser.”

A more efficient alternative

That’s where Musk’s biggest competitor comes into play. AST SpaceMobile has developed a direct-to-cell technology that utilizes large satellites called BlueBirds. These machines use thousands of antennas to deliver broadband coverage directly to standard mobile phones, says the company’s president, Scott Wisniewski.

“This approach is remarkably efficient: We can achieve global coverage with approximately 90 satellites, not thousands or even tens of thousands required by other systems,” Wisniewski writes in an email. McDowell agrees that AST SpaceMobile’s approach is more efficient and less wasteful.

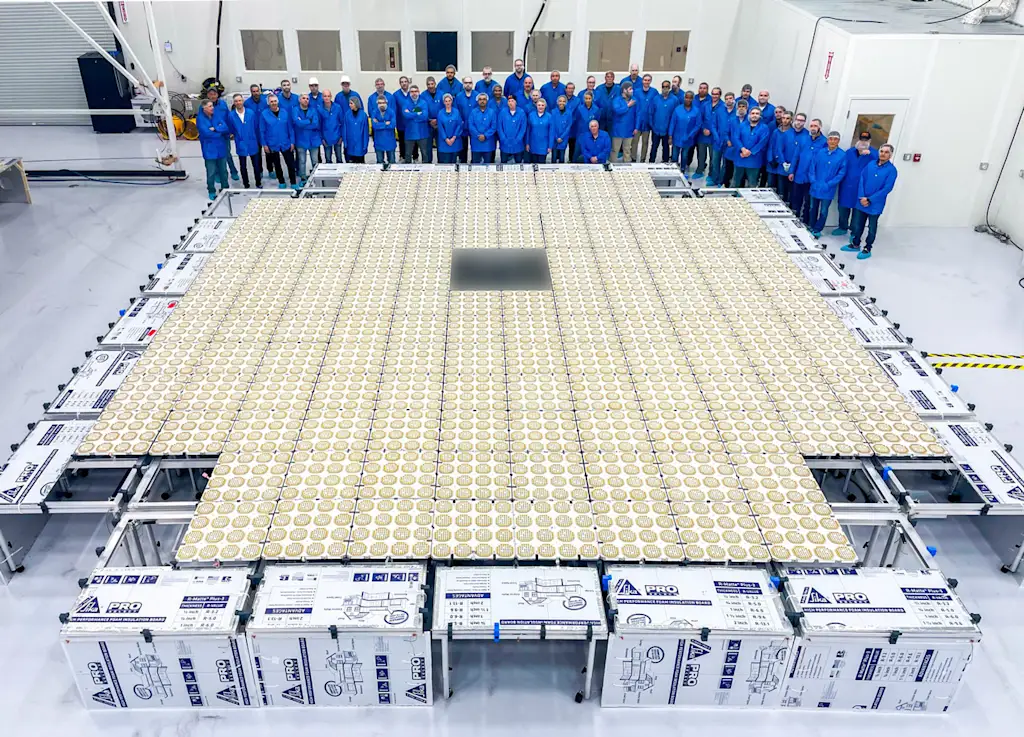

The key is its satellites’ size and sophistication. AST’s first generation of commercial satellite, the BlueBird 1-5, unfolds into a massive 693-square-foot array in space. Today, the company has five operational BlueBird 1-5 satellites in orbit, but its ambitions are much bigger. On December 24, 2025, AST launched the first of its next-generation satellites from India—called Block 2—and this one broke records. The BlueBird 6 has a surface of almost 2,400 square feet, making it the largest single satellite in low Earth orbit. The company plans to launch up to 60 more by the end of 2026.

“This large surface area is essential for gathering faint signals from standard, unmodified mobile phones on the ground,” Wisniewski explains. It is essentially a single, extremely powerful and sensitive cell tower in the sky, capable of serving a huge geographical area.

This design philosophy directly addresses the two greatest threats posed by the mega-constellation model. First, with only about 90 Block 2 satellites needed for global coverage, the sheer volume of material being launched and deorbited is orders of magnitude less than the tens of thousands planned by Starlink and others. With a 7- to 10-year lifespan, AST SpaceMobile’s satellites are designed to last longer than Starklink’s satellites, which have a lifespan of about 5 years. This combination of factors drastically reduces the potential for atmospheric pollution.

Additionally, a smaller number of satellites dramatically lowers the risk of orbital collisions. “Fewer satellites in orbit inherently reduces the probability of collisions and the creation of space debris, promoting a more sustainable orbital environment,” Wisniewski says. It is a solution built on precision engineering rather than brute numerical force, a testament to a different way of thinking about the problem.

As McDowell puts it, from a space traffic point of view, “Fewer, bigger satellites is probably better.” It is a design choice that prioritizes sustainability and risk mitigation.

A reckless, brute-force plan

The core idea behind Starlink’s direct-to-cell service is one of brute force. It is the digital equivalent of carpet-bombing: Saturate low Earth orbit with tens of thousands of relatively small, cheap, and disposable satellites. Each one acts like a tiny cell tower in the sky, talking to the phone in your pocket. Because they are in a low orbit, the lag is minimal, and the signal is strong enough for a standard phone. It’s a simple concept, but its elegance is deceptive. In reality, it has the elegance of a sledgehammer.

Starlink’s model relies on a constant cycle of replacement. The satellites are programmed to fall back to Earth after about five years, burning up on reentry. This is where the first major problem arises.

“When they burn up, they don’t just vanish,” McDowell explains. “They turn into dust, alumina dust, aluminum oxide particles. These particles are very good at destroying ozone.”

The long-term effect of depositing tons of this material into the upper atmosphere every single day is a terrifying unknown. We are, in effect, conducting an uncontrolled experiment on the protective layers of our own planet. McDowell notes that while a single rocket launch causes temporary, localized ozone damage, the continuous reentry of thousands of satellites creates a persistent, global problem that has never been studied on this scale.

SpaceX aggressively dismissed these concerns in 2021 in a legal battle with Viasat, a rival space internet service for home, business, and military use. Its legal defense directly attacked the scientific premise that burning satellites create harmful amounts of aluminum oxide. SpaceX has been ignoring warnings about potential ozone depletion since 2024.

However, the company has tried to address light pollution. When faced with an outcry from the astronomy community about its satellites’ brightness, it iterated on the design. First came DarkSat, an experimental coating that proved ineffective. Then came VisorSat, a deployable sunshade that blocked light from reflecting off the brightest parts of the satellite.

McDowell tells me that now SpaceX is using a dielectric mirror film that reflects less light back to Earth. “They have made a significant effort to reduce the brightness, and the newer Starlinks are substantially fainter than the early ones,” McDowell says. “But they are still bright enough to be a problem for the big survey telescopes like the Vera Rubin Observatory.”

These mitigation efforts, while commendable, address only one symptom of the problem—light pollution—and do nothing to solve the more fundamental issues of atmospheric pollution and orbital crowding. The problem is compounded by the fact that everyone is now copying the SpaceX model. Amazon’s Project Leo plans to launch more than 3,200 satellites.

Beijing and some Chinese companies are planning two separate mega-constellations, Guowang and G60 Starlink, totaling nearly 26,000 satellites. “We’re just at the beginning of this . . . so that gets very worrying because now it’s not just one company, it’s a whole bunch of companies,” McDowell warns. To add to his worries, just this week the Chinese government has applied for launch permits for 200,000 satellites.

To be clear, AST SpaceMobile’s approach is not without its own controversies. The sheer size of the company’s satellites makes them incredibly bright in the night sky, a significant source of frustration for ground-based astronomers. McDowell confirms that when it launched in 2022, AST’s prototype satellite, BlueWalker 3, became “one of the top 10 brightest objects in the night sky for a while.”

“It’s a serious issue, and we are working directly with the astronomy community to mitigate our impact,” Wisniewski says. The company is exploring solutions like anti-reflective coatings and operational adjustments to minimize the time its satellites are at maximum brightness. However, McDowell is not aware of anyone working with AST SpaceMobile, and the company didn’t provide any specifics.

According to McDowell, the size and brightness is a trade-off he believes is reasonable. “Although the BlueBirds are scary bright, there aren’t that many. So I kind of prefer that approach,” he says. “As long as they don’t turn around then and say, ‘Actually, we need 30,000 of these as well.’”

A game of orbital Russian roulette

Beyond the environmental concerns lies an even more immediate existential threat: Kessler Syndrome. Popularized by the movie Gravity, it is a scenario that keeps space experts like McDowell up at night. The theory, proposed by NASA scientist Donald Kessler in 1978, describes a domino effect where a collision between two objects in orbit creates a cloud of debris. Each piece of that debris then becomes a projectile that can cause another collision, creating even more debris, until low Earth orbit becomes an impassable minefield of hypervelocity shrapnel.

“The more satellites you have, the more the chance of a collision,” McDowell states plainly. “And the problem is once you have the first collision, the debris from that is now threatening all the other satellites.”

SpaceX has engineered a highly automated collision avoidance system for Starlink, and McDowell acknowledges its sophistication. The company’s satellites constantly monitor their trajectories and can autonomously fire their thrusters to dodge potential impacts. “They do thousands of maneuvers a month,” he says, which is a testament to both the system’s capability and the terrifyingly crowded environment it operates in. In total, Starlink satellites have performed 50,000 evasive maneuvers since 2019.

But while SpaceX claims that its satellites are 100% safe, the facts tell us that they are not foolproof. “Even with a 99% success rate for deorbiting, a 1% failure rate on a 30,000-satellite constellation means you’re adding 300 dead, multi-hundred-kilogram satellites to orbit every five years,” McDowell says. That’s 300 uncontrollable bullets waiting to start the Kessler Syndrome.

A catastrophic chain reaction could, in a matter of hours or days, wipe out the essential satellite networks that underpin modern civilization. This isn’t just about losing your GPS navigation on the way to a new restaurant. It’s about the collapse of global finance, weather forecasting, communications, and critical military and disaster-response systems. We are talking about a technological regression of decades, a scenario McDowell finds increasingly plausible as more mega-constellations are launched. It’s a high-stakes gamble with civilization’s essential infrastructure.

There’s also a direct-hit danger for people on the ground. A few Starlink satellites have already failed in orbit, becoming uncontrollable space junk that fell back to Earth. There’s at least one report of a piece of a satellite hitting a building in Canada. The latest reported incident took place on December 17, 2025, when a Starlink satellite experienced an anomaly, losing communication and causing a propulsion tank vent, rapid orbital decay, and the release of debris in low Earth orbit. In a 2023 report to congress, the Federal Aviation Administration said there’s a real risk of falling Starlink debris injuring or killing someone by 2035.

Space junk is also a problem for rockets. In early November, <a href="https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/chinas-shenzhou-20-crew-return-friday-after-space-debris-delays-mission-2025-11-14/#:~:text=BEIJING%2FWASHINGTON%2C%20Nov%2014%20(,according%20to%20state%20broadcaster%20CCTV." target="_blank" re

source https://www.fastcompany.com/91464903/space-cellphone-war-ast-spacemobile-starlink

Discover more from The Veteran-Owned Business Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.