In the fall of 2024, six college students joined forces to start an AI company together. Five of them had met while studying computer science, computer engineering, and electrical engineering at Georgia Tech in Atlanta. The sixth, its CEO, was pursuing a degree in childhood and adolescent development at Sacramento State, with an eye on becoming a grade-school teacher. That wasn’t the only thing that made him an outlier. He also happened to have been in the tech industry for well over thirty years—longer than his fellow founders had been alive.

The Georgia Tech students are Ian Boraks, Jacob Justice, Drake Kelly, Ella McCheney, and Abhinav Vemulapalli, all of whom happen to be 21. The Sac State student/tech veteran is Bill Nguyen, whose past startups amount to a guided tour of Silicon Valley trends over the years, from “push” technology to unified messaging to digital music to social networking to telehealth. Their new company, Olive.is—Olive for short—is developing technology to make AI better at grasping the full meaning of spoken communications, as conveyed by elements, such as inflection and dialect, that current models may gloss over. It plans to offer its tech as a service for enriching AI-powered applications in education and other areas.

Olive’s name references the company’s ambitious hope of fostering better understanding—an olive branch, if you will—between humans and machines. It’s still in the process of researching and developing its AI model, and has raised $5 million in seed funding from education-focused venture capital firm Owl Ventures and Georgia Tech. The unusual founding team was a selling point to Owl, which also backed one of Nguyen’s previous ventures, Hazel Health.

As students themselves, the Georgia Tech founders “are deeply connected and have a lot of recency with the ideal cohort of potential users that are going to benefit from all this technology,” says Owl’s Lyman Missimer. “But Bill is giving this team the full kind of Silicon Valley hustle out in the middle of Atlanta.”

More than words can say

When I first met Nguyen in 2006, he was already a Silicon Valley vet and burbling with enthusiasm for a company he’d founded called Lala, which helped people trade CDs through the mail. (It later moved into music streaming and was acquired by Apple in 2009.) His knack for high-energy pitchmanship helped his next company, the location-based, photo-centric social network Color, raise $41 million from firms such as Sequoia. It was ultimately best known for crashing and burning, as detailed in a 2011 Fast Company feature by Danielle Sacks.

Today, Nguyen is as exuberant as ever when discussing Olive’s goals and origin story, and doesn’t seem to have aged nearly 20 years since our earliest encounter. As he explains it, AI models for turning speech into text, such as OpenAI’s Whisper, have gotten uncannily good at correctly transcribing the literal meaning of what they hear. Yet the words we choose hardly convey our intent all by themselves. Elements such as inflection matter, too—and are sometimes absolutely crucial to understanding what someone is trying to say.

“There’s definitely a lot in human conversation that gets chopped off by LLMs,” says Nguyen. “For example, if you ask me a question and I go, “Yeeeeeees?”—he infuses the word with uncertainty—“it’s not really a ‘Yes.’ But an automated speech recognition system will basically truncate all that nuance, get rid of it, and just put it as a ’Yes.‘”

If existing LLMs struggle with some of the subtleties of how we talk to each other, it’s at least in part because they’ve been trained on material that’s publicly available in vast quantities, such as podcasts. Such recordings “probably sound really, really clean and they’re great audio,” says Nguyen. “But that’s not how we actually converse.”

Nguyen’s interest in this current limitation of AI is intertwined with his long-standing passion for education. Years before he went back to school to become a teacher himself—he’s halfway to earning his degree—he cofounded a public charter school near Lake Tahoe. As a result, he learned that few doctors in the area accepted Medicaid, greatly limiting student access to healthcare. That helped catalyze Hazel Health, which provides telehealth services through K-12 schools. It now serves 5,000 of them in 19 states.

The Hazel experience left Nguyen attuned to the real-world challenges schools face as they adopt technology. He provides an example relating to speech recognition. “In a school district, one of the things that they have to focus on is the ability to understand when to do an intervention for a student around reading,” he says. In theory, AI might help by analyzing audio of them speaking. But only if it understands what they’re saying, regardless of whether ”a student has a Mexican-American vernacular, African-American English vernacular, or Hawaiian vernacular.“

To complicate matters, “Children are especially hard [for AI to understand], because they have very limited vocabulary,” says cofounder McChesney. “So in order to express themselves, they find more creative ways to use words. And so what we’ve seen is that that can mean that models misinterpret them more, which can have negative consequences, especially when teachers are trying to leverage these tools to help them bring better experiences to the classroom.”

The glimmer of opportunity in the idea of training AI models using audio that reflects how real people talk—especially students—led to Olive’s founding. How Nguyen, based in Tahoe, ended up collaborating with a bunch of young techies in Atlanta is a story in itself. At first, he noodled on the idea with Justice, who is his son as well as a fellow Olive founder. As they forged ahead, the project expanded to include more people from Justice’s social circle.

McChesney, whose credentials include high-school work at the Department of Defense and four years interning at Lockheed Martin, had recently returned from a study trip to Korea when she joined the effort, right as Nguyen was prepping to pitch the company to investors. “I got a text while I was in Costco from Drake, and he’s like, ‘Bill wants your résumé, send it in the next 10 minutes,” she remembers. “Which would’ve been great if I wasn’t in a Costco with my phone at 5% and no cell service, because Costco is a giant steel box.” She Airdropped her CV to a friend, who sent it to Nguyen just in time.

The Atlanta-based cofounders do much of their partnering with Nguyen over Discord, though they quickly ran into the limitations of typed messages as a form of collaboration. In their minds, that only underlined the richness of verbal communications and the importance of teaching AI to comprehend it.

“We’d always end up doing late-night calls, because that was the easiest way to communicate amongst ourselves, and the easiest way to really get our ideas across and understand what people are saying,” says McChesney. “There’s no ambiguity, the way there is in a lot of these text messages, and we can iterate faster. That really inspired what we’re trying to do here.”

It’s all in the data

To overcome current AI models’ limitations when it comes to capturing how humans express themselves verbally, Olive had to start with better data. More specifically, it had to start with raw audio of people talking to each other in unscripted situations. “Our whole idea was if we can get really clean data sets, if we don’t remove any of the information, if we train a model that actually retains all of this context, then we can solve these mission-critical cases,” says Nguyen.

More specifically, it decided to start with audio recordings of students engaged in conversations with professionals such as teachers and therapists—recorded, it stresses, with the participants’ permission and awareness that they could be used for training.

As the company was finding sources of such material, Nguyen’s background at Hazel Health came in handy. “We worked with school districts, we worked with universities,” he says. “The data set is pretty extensive now. It’s north of 40,000 hours.”

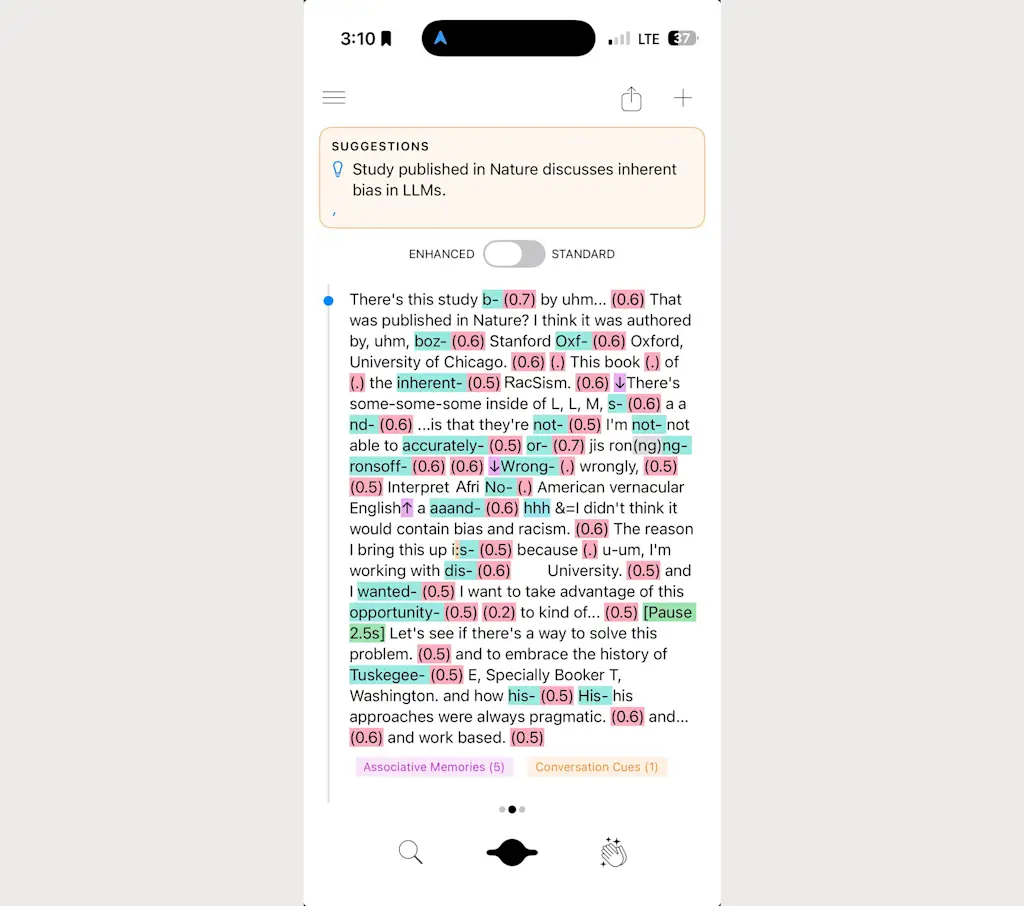

The company also built an iPhone app of its own, which I tried in pre-release form. Taking advantage of the beefy AI capabilities of Apple’s newest smartphone chips, it builds an understanding of the user’s needs by applying Olive’s models to verbal input. All processing is done on the phone, and input isn’t used for training purposes.

Olive doesn’t see this app replacing other AI tools so much as enhancing them. For instance, you could talk into the Olive app at length about an app you’d like to create, then have it turn your verbal meanderings into a product requirements document to feed into a vibe-coding platform. “You‘re using your voice to have a more engaging conversation and actually hash it out,” says McChesney. “That’s what makes this so cool.”

However, Olive isn’t building its business around this iPhone app. Nor does it intend to provide fully-baked applications based on its technology. Instead, it plans to offer its AI model as a cloud-based service. Other companies will be able to use it as a technological layer in their own creations, providing them with a deeper understanding of speech than they’d get by relying entirely on existing voice models.

Along with possible uses in education—ranging from tutoring to helping scale up college counseling—Olive is targeting hiring, healthcare, and finance as areas where it hopes to find customers. “These are all high stakes, and they’re all regulated in terms of what you can do,” says Nguyen.

They’re also all places where the limitations of existing AI may introduce harm that Olive hopes to overcome through better, fairer comprehension of a wider range of communications styles. “You want AI access to be more equitable,” says McChesney. “You want everyone to be able to leverage these tools, because these tools are inherently part of our workforce.”

The company’s home page is currently devoted to a sobering blog post, “Covert Racism: The Voice Inside the Machine.” Heavily footnoted, it cites research that shows how prejudices are baked into AI in ways that can be difficult to detect even if its creators are actively trying to combat bias.

“The part of it that’s mind-blowing to me is people are not getting jobs,” Nguyen says. “People are getting declined on loans. People are having adverse health effects. And no one knows why.”

Olive’s potential to steer AI in a better direction might be particularly relevant in education, where the technology is still in the process of finding applications and the company has a shot at being foundational. ”Every major new technological shift is developed, built, and scaled, and then 10 years later it finally finds its way into education,” says Owl Ventures’ Missimer. “When we saw what Bill and team were building, we knew that the edtech market couldn’t wait 10 years for this type of technology, especially in a time where voice is becoming such a larger part of the technological stack.”

With that in mind, Owl is helping to introduce Olive to other companies in its portfolio of education startups. They include Amira Learning, a 2025 Fast Company Next Big Things in Tech honoree that offers a suite of AI and neuroscience-based reading aids.

Given that Olive’s strategy is to provide its AI model as an ingredient for other companies’ products, those kinds of relationships have everything to do with its long-term fate. For now, it remains tiny, though it’s already grown to nine people. Nguyen says he’s reveling in the hands-on experience of running something so tiny.

At his previous, larger startups, “I, as the founder, was pretty separated from the actual engineering process,” says Nguyen, who is not an engineer by background. “But now I’m not. I’m in the code base. I check it every day. I know what’s happening with it.”

Once again, he exudes enthusiasm. Once again, he’s working on something that taps into the tech industry’s current obsession. Nguyen, who dubbed himself “the Don Quixote of startups” in Sacks’ 2011 article, may not be destined to run Olive forever. (Did I mention his intention to become a grade-school teacher?) But if this startup takes flight, having helping his youthful cofounders get it off the ground will be a legacy in itself.

source https://www.fastcompany.com/91464353/olive-is-bill-nguyen-voice-ai-education

Discover more from The Veteran-Owned Business Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.