High-power magnets undergird an enormous amount of modern society. From high-end audio speakers to electric vehicles, wind turbines, and fighter jets, they are a vital component in much of the technology we touch every day. To make them requires mining and refining rare earth elements—a supply chain largely controlled by China.

Companies around the world are racing to find alternatives by using materials that are more abundant and cheaper to produce domestically. Minneapolis-based Niron Magnetics believes it has found a solution, claiming it can approach key aspects of rare earth magnet performance, using humble iron and nitrogen—albeit in an exotic formulation. General Motors, Stellantis, the U.S. government, and others are betting on it.

“The Chinese put export controls in place around rare earths, and that’s been a great benefit to us,” says Niron CEO Jonathan Rowntree.

China currently accounts for around 60% of global rare earth mining, according to the International Energy Agency, and about 90% of refining (including ore mined in and shipped from the U.S.). It also supplies over 90% of rare earth magnets, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Geopolitical tensions are putting that supply in jeopardy.

“We want to be able to solve this problem for Western companies as quickly as possible,” Rowntree says. When asked if Niron will only serve the West, he says, “All these countries outside of China have the same problem.” Beyond the U.S., Niron plans to build one factory somewhere in Europe and another in Asia. “It won’t be in China. It’ll be in Southeast Asia, most likely,” he says.

Moving beyond neodymium

Companies—and governments—are especially chasing alternatives to one of these rare earth metals: neodymium. It is alloyed with two other metals to make the world’s most popular magnet. “Neodymium iron boron is the best permanent magnet going. And no one’s really got anywhere close,” says Nicola Morley, professor of materials physics at the University of Sheffield in England. She has no affiliation with Niron.

Niron has raised approximately $200 million from private funders and about $100 million from federal and state tax credits or grants, including from the departments of Energy and Defense, to build its exotic formulation over the past 15 years.

The world could finally find out how well Niron’s technology works in 2026, when it says that magnets from its pilot facility in Minneapolis will start to appear in home audio speakers. Motors in appliances such as washing machines, clothes dryers, and air conditioners are on schedule to follow in 2026 or 2027.

Niron broke ground on its first full-scale factory in Sartell, Minnesota, in September, and expects to be churning out 1,500 tons of magnets per year by early to mid-2027. It’s considering several states for its next 10,000-ton-per-year “world-scale” plant, which it estimates could provide more than 20% of U.S. supply after it opens in 2029. Then will come the plants in Europe and Asia. Niron has no plans to license its technology. “We want to be a full-service magnet producer,” Rowntree says.

Dates for when additional plants will open are not certain, or for when magnets may appear in industrial machinery, cars, planes, and windmills. Rowntree says that, compared with the short product cycle for consumer tech, “industrial [is] medium, automotive takes a bit longer, and then defense and wind turbines take the longest.” Niron says only that it is “engaged” with defense contractors.

Building a rival magnet

Things get technical rather quickly when discussing Niron. But details matter in order to determine if it can achieve its ambitious business goals, including going public, which Rowntree says is “a few years away.”

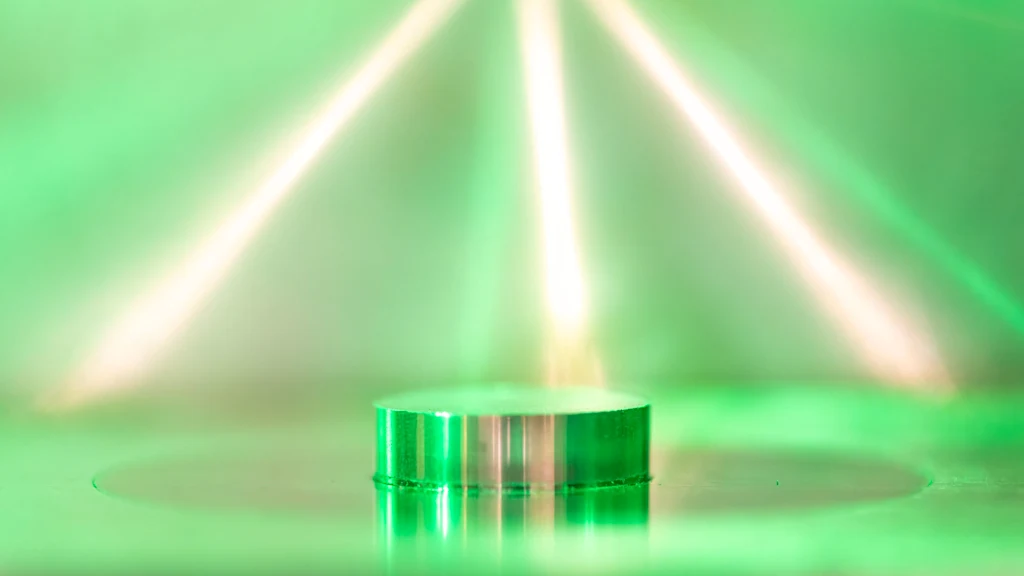

Niron has several patents for iron nitride technology, including one for how to manufacture a particular arrangement of the chemical compound—both within the molecules and in how they form crystals—by getting and keeping it in what’s called an “alpha double prime phase.”

Rowntree puts that in somewhat simpler terms, saying the atoms are “arranged in such a structure that the nitrogen atoms kind of flex the structure” to cause greater magnetism. This is similar to neodymium magnets, in which, as Morley puts it, “boron basically stretches” the structure of the crystals.

Getting these tiny crystals into large magnets was another challenge. All high-performance magnet making starts with material in powder form. Next, a magnetic field is applied to align these grains, so their magnetic poles all face the same way. Then the grains are compressed. Finally, in rare earth magnets, high heat is applied to stick the grains together.

But heat would wreck Niron’s material, so the company’s scientists developed a work-around for compacting the magnets. “There was, I would say, secret sauce in manufacturing of the nano scale, the phase that we want, and keeping that phase,” Rowntree says. “And then a lot of technology around, ‘How do you cost-effectively scale that?’”

Will the magnets work?

Niron has revealed data on the strength of its initial magnets, which is on the lower end of neodymium’s performance. It expects to eventually approach neodymium’s level, which will make it a worthy competitor.

What Niron has not yet revealed publicly is how well the magnets can hold up when exposed to strong magnetic fields in devices like EV motors. At a certain point, stresses like these can jumble the tiny regions of magnetism in any magnet so that they cancel each other out and turn it into just a lump of useless metal.

Niron says its magnet’s ability to resist getting demagnetized at room temperature will never be as good as with rare earth metals, but it aims to get close enough.

So Niron is starting by putting its magnets in speakers, because they produce a smaller magnetic field, while working to improve its numbers for “more demanding applications.” The company says it can replace weaker magnets, so low-end speakers can be smaller or perform better, but says it will also replace the more powerful rare earth magnets in higher-end speakers.

As for more demanding applications, Niron and Stellantis announced in October a collaboration to develop new motor designs for EVs. Stellantis said simply that this “allows us to explore the possibilities.”

Niron says its tech could replace neodymium magnets in some aircraft components, too, but not the jet engine. It gets too hot for both magnet types and requires an even pricier rare earth metal: samarium.

Providing magnets for autos and planes (and wind turbines) is still years in the future. But if audio gear makers keep to the schedule Niron is forecasting, many questions will be answered next year. “Once these magnets hit the market, they can be studied independently by others, which will be important for the industry,” Morley says.

Discover more from The Veteran-Owned Business Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.