For an architect whose name and work have become known all over the world by laypeople and architecture fans alike, Frank Gehry’s buildings are about as far from the mainstream as one can get. Bent, curved, and clad in shiny metal, the most famous buildings by Gehry, who died last week at 96, are also the most improbable.

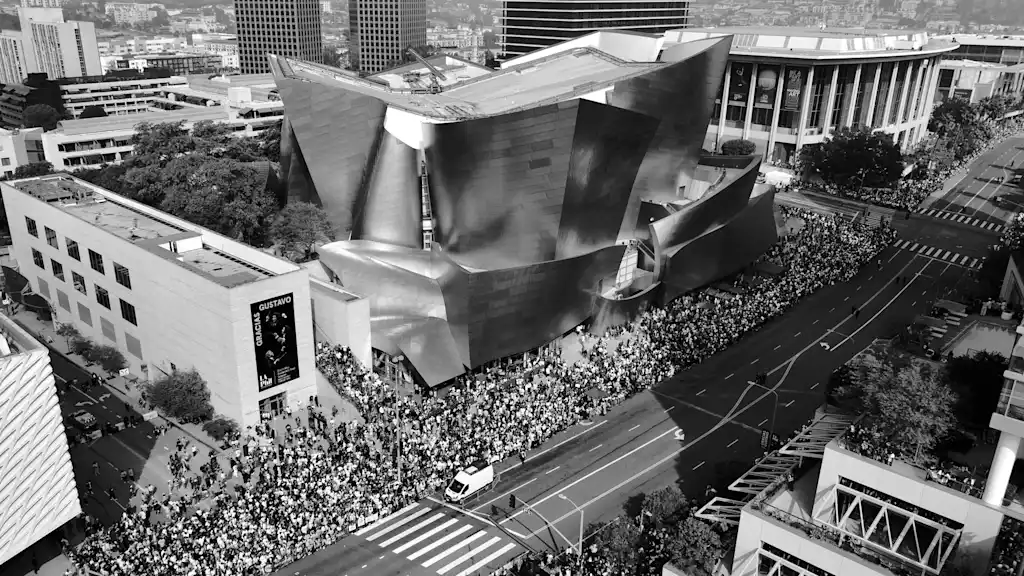

Coming up with the flamboyant designs for landmark buildings like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles was only part of what made Gehry one of the most successful and celebrated architects in American history. Just as impressive are the ways Gehry helped explore and expand the architecture technologies used to actually build those swooping designs—revolutionizing the practice of architecture in the process.

Gehry worked for decades to advance new technologies and project management approaches that radically changed how architects work and the inventiveness they’ve been able to bring to modern buildings. “On the technology front he was really a pioneer,” says Aviad Almagor, vice president of innovation at the construction technology company Trimble.

A visionary luddite

Despite claiming a near-incomprehension of computers, Gehry and his Los Angeles-based firm, Gehry Partners, have been at the forefront of applying high-end technology solutions to architectural design, engineering, project management, and construction since the 1980s.

Gehry was one of the earliest architects to experiment with and embrace computer-aided design approaches like optimizing outcomes through parametric design and digitizing designs from concept to construction through building information modeling. These are now standard practices in the world of architecture, but when Gehry and his firm started applying these approaches it was uncharted territory for the field.

The breakthrough for Gehry came after his firm won a commission to design a large pavilion for the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. Gehry, a sculptor at heart, designed a massive abstract fish to be built using stainless steel mesh panels. Translating the design concept into a buildable set of two-dimensional blueprints proved complicated. According to an article on the project from Priceonomics, a contractor tried to build a mockup of the project six times, but couldn’t get it right.

So Gehry’s team found a solution in a software tool developed by an aerospace manufacturer. Creating an advanced 3D model of the project allowed Gehry and his firm to more clearly communicate the precise shapes and curves of his design to the builders and contractors on the construction site. The project was completed on time and on budget.

It was a transformative change for Gehry and his firm, which then used the approach to bring 3D models of its projects past the design phase and use them all the way through construction. This streamlined the designs of his most complicated buildings, while also minimizing the change orders that could have hampered their fidelity during construction.

Gehry used this approach on his next major project, his breakthrough masterpiece design for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, which opened in 1997. With a highly complex physical form and an exterior designed to be made form thousands of intricately bent and curved sheets of titanium, the design was anything but straightforward. An advanced 3D model of the project became an early version of building information modeling, or BIM, creating a single source of information about the design that could be used by the architects as well as the trades people and contractors who built the project.

It made a seemingly impossible project possible, according to Samuel Omans, head of AI growth strategy at Autodesk, the architecture, engineering, and construction software company behind industry standard design tools like AutoCAD and Revit. “There was no way at that time that he could communicate the cut sheets and fabrication requirements necessary for that external cladding to the manufacturers and to the folks in the field using 2D drawings,” Omans says. “It just wasn’t possible.”

During an interview for Wallpaper magazine at his L.A. studio in 2011, Gehry told me this BIM approach reinvented his practice. “That gave us more of a measure of control. It gave us the tools to control our process,” he said. “And I thought that was only valuable to my kind of work because I do very special shapes, but we’ve found over the years that it’s valuable to everyone.”

Technology as a service

That realization led Gehry’s firm to turn its expertise into a service. In 2002, the firm spun off a subsidiary called Gehry Technologies, which created an architecture-specific 3D modeling tool based off its experience designing with software built for the aerospace industry, as well as a cloud-based collaboration platform to take those 3D models from design concept to built project. Outside clients, including architecture firms ostensibly in competition with Gehry’s for big projects, streamed in to take advantage of the new toolset. In 2014, Trimble acquired Gehry Technologies for an undisclosed sum.

“Bilbao is obviously one very famous project, but there were many others where this kind of technology was needed,” says Trimble’s Almagor, who was involved in the acquisition. “They provided services to support those complex projects and help create a much more efficient project without cost overruns, without schedule delays. It really dramatically changed the way a project can be delivered, and this industry is really challenged by cost and schedule.”

Gehry’s architecture technology is now the basis of cloud-based design collaboration tools used by more than a million Trimble customers, and has influenced the shape of 3D design software produced by Autodesk, which had a partnership with Gehry Technologies in 2011. “They were a big part in helping to bring some of our software to the wider market,” says Omans, who is also on the faculty of Yale’s architecture school.

He says as contemporary architects have embraced a wider range of inventive forms, this kind of technology has made it more feasible to turn inventive ideas into physical buildings. “The technology was able to drive more and more aesthetic experimentation . . . That approach to the model as the deliverable was absolutely fundamental in delivering some of the most complex projects of the last 25 years.”

As an architect, Omans collaborated with Gehry’s firm several times over the years, and says this emphasis on technology stood in contrast to the analog design style of Gehry himself. “He would sit down with you and he’d be ripping paper apart and he’d be crunching up paper and he’d be drawing and sketching,” he says.

“The technology kind of allowed him to become an orchestrator of these data-rich prototype models, not just not just the maker of drawings,” Omans adds. “For Frank, this was technology supporting creativity.”

Without that technology, it’s hard to imagine many of Gehry’s best known works ever moving past the stage of one of those hand-made models. Even so, Gehry, who was born in 1929, kept his distance from the computers that enabled so much of his creative success. “I don’t know how to turn it on, or how to use it,” Gehry told me back in 2011. “It complicates my life.”

Discover more from The Veteran-Owned Business Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.